Allegations that two former Twitter employees spied on users for the Saudi government have spotlighted the threat posed by insiders who exploit their access to the mountains of sensitive data held by tech companies.

The Twitter case adds an alarming international dimension to the longstanding problem of rogue employees who steal information or snoop on others.

"It's stupid to think foreign intelligence services would spend tens of millions trying to hack a company like Twitter when they can pay less than $100,000 to bribe employees," cybersecurity expert Robert Graham of Errata Security said Thursday.

Detecting insider access isn't easy, despite the availability of tools to do so, experts say. Yet the wealth of data that these companies have turned them into lucrative targets.

Companies that provide email, social media, search and other services have troves of personal data, including users' location, hobbies, political views and connections to other users. Many services also have users' private emails and other conversations.

While activists fearing repercussions might use a pseudonym in public posts, that's ultimately tied to a real account. An employee can look up the email address or phone number used to sign up and the locations used to access the app.

The coordinated spying effort unveiled Wednesday included the user data of over 6,000 Twitter users, including at least 33 usernames for which Saudi Arabian law enforcement had submitted emergency disclosure requests to Twitter, investigators said.

Most big tech platforms already take measures to prevent employees from abusing their position to spy on a crush they saw on Tinder.

Detecting well-instructed moles working for foreign governments is a "whole different kind of problem" because they may be cannier about what data they access and how to justify it, said John Scott-Railton, a researcher with the internet watchdog Citizen Lab.

He said companies can erode collaboration and trust if they put up too many silos, but they become a target if they put up too few.

Wednesday's federal complaint in San Francisco alleged that the Twitter employees were able to access the private data, including a user's email account, despite holding jobs that didn't require access to Twitter users' private information. That violated company policy, according to the complaint.

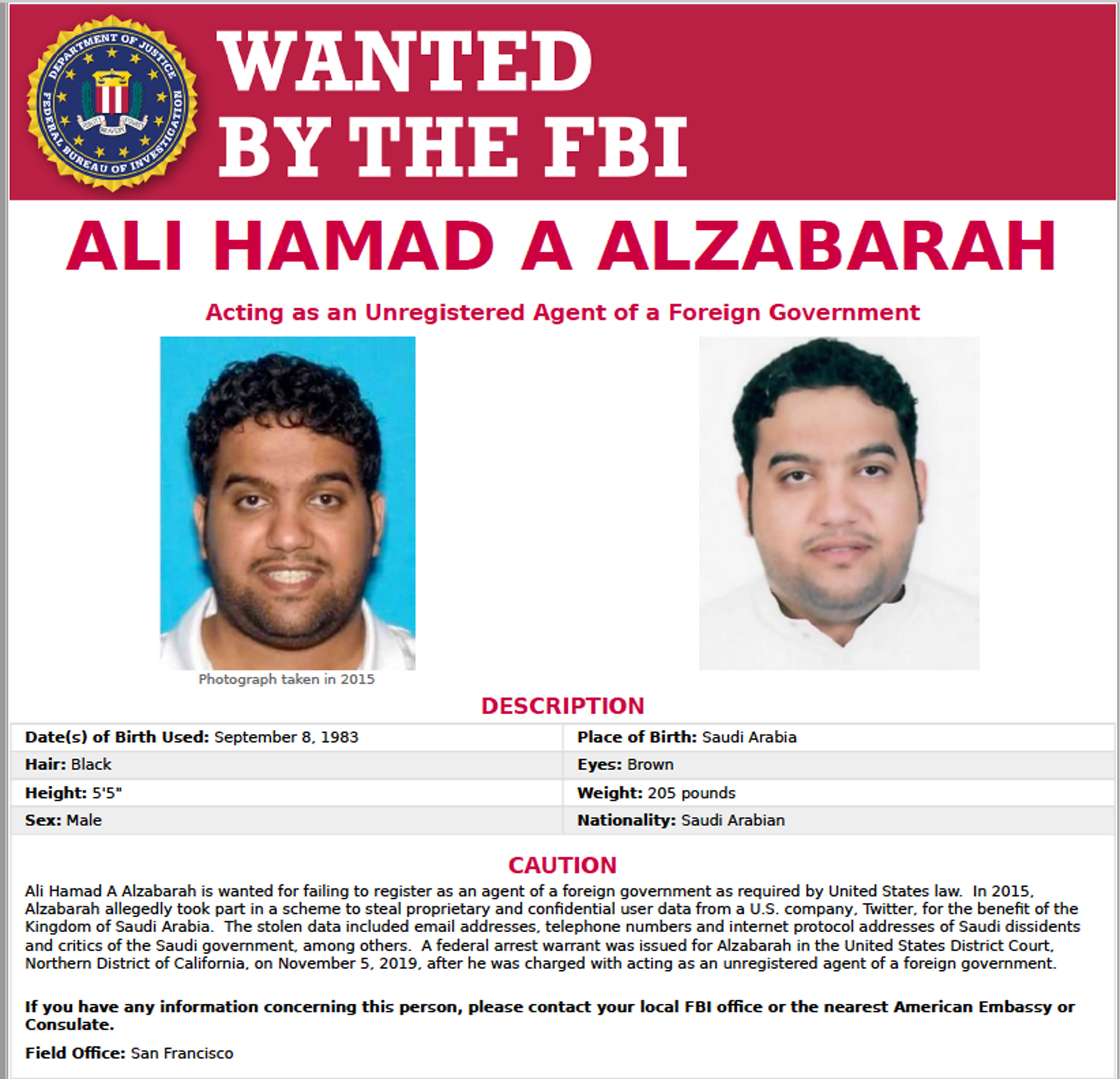

Ahmad Abouammo and Ali Alzabarah were charged with acting as agents of Saudi Arabia without registering with the U.S. government. Prosecutors say they were rewarded by Saudi royal officials with a designer watch and tens of thousands of dollars funneled into secret bank accounts.

Twitter said in a statement that it "limits access to sensitive account information to a limited group of trained and vetted employees," but declined to elaborate on how the breach described by prosecutors happened. A year ago, after reports first surfaced of Twitter insiders targeting Saudi dissidents on the platform, the company said that "no other personnel have the ability to access this information, regardless of where they operate."

It's not clear how Twitter's security practices compare to other tech giants or if they have improved since 2015, when Abouammo and Alzabarah stopped working at the San Francisco company.

Google, Facebook and Apple didn't respond to email and phone requests for comment Thursday on how they prevent rogue employees from accessing users' email and other online services. Microsoft, which owns LinkedIn, declined comment.

"We should not assume that the Saudi government is the only government that has thought about doing this," said Suzanne Spaulding, a former undersecretary for cybersecurity at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Spaulding said tech companies that are holding so much private data need to do a better job of segregating that data and limiting who can see it. "These are people who didn't need access to this information to do their job," she said of the indicted former Twitter employees.

Jake Williams, president of Rendition Infosec and a former U.S. government hacker, said no one should be surprised when a foreign intelligence service infiltrates a big tech company. He said better auditing inside company networks can detect the espionage.

"Too often, logging is written purely for the purposes of troubleshooting outages and service issues, not tracking insiders," he said.

But Tarik Saleh, a security engineer at DomainTools, said it takes resources for companies to look for anomalies in employees' access to data. While artificial intelligence systems in recent years have had moderate success in automatically scanning for unusual activity, "once you're in the weeds, it's extremely difficult," he said. "Very few organizations can do it right, even sophisticated ones like the NSA or the CIA."

Tony Cole, chief technical officer at Attivo Networks, said that rather than focus solely on detecting unauthorized access, it's better for companies to limit data access to authorized individuals to begin with. Such systems can also flag unauthorized attempts, he said.

Some cybersecurity firms offer not just monitoring but active measures to try to detect employee misbehavior — such as introducing as bait bogus data with commercial value and seeing if workers suspected of previous wrongdoing take that bait, said Alex Holden, chief security officer of Hold Security in Milwaukee.

Experts said tech companies — particularly social media and email providers — must recognize that they will be targets of insider threats given the types of information they hold.

"We've talked to them about it for years and they've kind of listened with half an ear maybe," former FBI counterintelligence agent Frank Montoya said.

Holden said the new cases of data abuse that pop up every month point to "a certain amount carelessness among companies."

Facebook recently made headlines when it disclosed that it had left millions of user passwords exposed on its network in plaintext that should have been encrypted.

And then there was the CapitalOne hack, in which a former Amazon Web Services employee who knew her way around the network stands accused of obtaining records on roughly 100 million people.

Until recently, tech companies were also routinely letting employees and contractors review users' audio interactions with digital assistants. While that was done to improve services, many of the conversations leaked. Companies scaled back their practices and offered better disclosures only after news reports emerged.

Source