NEW YORK — The day before he went out to protest, Colinford Mattis, 32, an Ivy-educated corporate lawyer in Brooklyn, chatted for over an hour on the phone with a close high school friend. They discussed George Floyd’s death as just “another example of an unarmed black person being killed,” the friend said, but they talked about grocery shopping and YouTube videos as well.

The next afternoon, Urooj Rahman, 31, who is also a lawyer and Mattis’ close friend, attended a Zoom talk about building “solidarity movements” between people of color. Rahman had recently finished fasting for Ramadan and was caring for her mother at home, also in Brooklyn.

What happened next came as a surprise to many who know the two young lawyers.

The pair took to the streets May 29 with thousands of New Yorkers who were voicing their outrage over Floyd’s death. But after midnight, police officers spotted them in a tan minivan driving through the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn. At one point, Rahman climbed out, walked toward an empty police patrol car and threw a Molotov cocktail through its broken window, prosecutors said.

Their arrests shortly after were a startling turn for the two, who were otherwise role models in their communities. Both children of immigrants, they rose from working-class Brooklyn neighborhoods to win a long list of awards and campus leadership positions. Mattis graduated from Princeton University and New York University Law School, while Rahman went to Fordham University for college and law school.

As one friend put it, they were “NYC kids from impoverished backgrounds who made something of themselves.”

A little over a week after their arrests, it is difficult to draw conclusions about their motivations. If the charges prove to be true, were the two spurred by an ill-advised moment of anger — or did they act out of a deeper, darker disillusionment with the political system in the wake of Floyd’s death?

A portrait of Mattis and Rahman was assembled from interviews with more than three dozen of their friends, relatives, colleagues, neighbors and former professors. Those who knew the two well said they had long been passionate about social justice issues and had expressed frustration over Floyd’s death but never showed a desire to commit violence.

Investigators have been scrutinizing their social media accounts and personal backgrounds to determine whether the pair had been involved with groups that espoused violence, according to law enforcement officials briefed on the investigation. But they appear to have found no evidence of such ties, and prosecutors did not offer a motive in court filings.

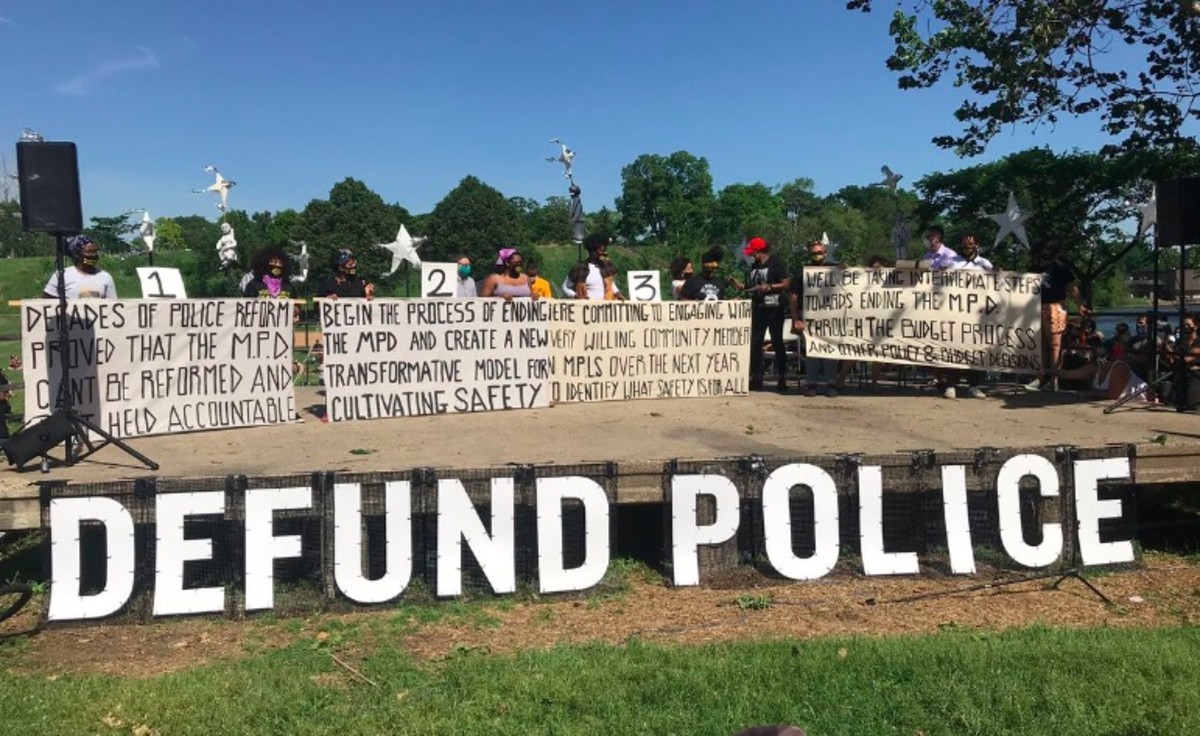

Still, in a video interview with Loudlabs News NYC, first reported by The New York Post, less than an hour before the attack, Rahman said it was understandable for people to be in the streets and enraged about police brutality.

“This has got to stop, and the only way they hear, the only way they hear us, is through violence, through the means that they use,” she said.

She suggested that the destruction of police property was appropriate.

“People are angry because the police are never held accountable,” she said.

In the video, she was standing near a convenience store, according to people with knowledge of the investigation, where some of the materials for the attack were purchased.

At a hearing last week, a lawyer for Rahman all but acknowledged her guilt, suggesting that the two had foolishly engaged in a reckless act.

“This was lawless; this was stupid,” said the lawyer, Paul Shechtman. “This was two people swept up in the moment. But it is two people with no history of violence, no criminal history at all.”

Mattis’ lawyer, Sabrina Shroff, said at an earlier hearing, “The government tries to argue to this court that Mr. Mattis’ behavior — assuming that they can prove it beyond a reasonable doubt and conceding nothing at this point — is indicative of who Mr. Mattis is. They are clearly wrong.”

Since the arrest of the two, friends and family members are struggling to understand what happened.

Ikenna Iheoma, the friend who spoke with Mattis the day before the protest, said they had never discussed violence against police. “We went to private high school,” he said. “That’s not the lane we go to. We try to intellectualize and come up with policy solutions.”

Friends said Mattis had sounded relatively upbeat since the coronavirus outbreak began, even after he was furloughed without pay March 31 from his job as an associate at the law firm Pryor Cashman LLP. Mattis had been working on multimillion-dollar deals, including the acquisition last year of the fashion brand Anne Klein.

Several friends said Mattis had not told them that he had lost his job. He did, however, tell one friend in April that he was already interviewing at other firms.

Mattis, a reliable presence at Princeton’s boisterous annual reunions, had been planning to attend a virtual event for his 10-year reunion on the day he was arrested, friends said.

Salmah Rizvi Urooj Rahman

Salmah Rizvi, who was also at the May 29 Zoom talk with Rahman, said nothing seemed unusual about Rahman’s recent behavior.

“She was in a good spiritual state this past month,” said Rizvi, who called Rahman her best friend. “She’s always been vocal about the important role of nonviolent resistance in seeking change.”

Rahman was a staff lawyer at Bronx Legal Services, helping poor tenants facing evictions. Her supervisor, Jackeline Solivan, said she was deeply committed to the job and, like other colleagues, had been stressed about pressures on her clients caused by the outbreak.

Friends said they were not aware that the two were going to attend the protest that Friday, the second night of demonstrations in New York City.

While the previous night had been quiet, the scene at Barclays Center in Brooklyn turned chaotic on that second day. Videos on social media showed police beating protesters with batons and protesters throwing bottles and debris at police.

In the middle of the chaos, shortly after midnight, Mattis and Rahman, while riding around in his minivan, pulled over near the 88th police precinct at Classon and DeKalb avenues.

Rahman stepped out of the passenger seat and threw a Molotov cocktail through the broken window of an empty police car, setting the dashboard on fire, according to prosecutors, who said the episode was captured on surveillance video. No one was injured.

Inside the van, police also found a Bud Light beer bottle filled with toilet paper, a liquid believed to be gasoline and a lighter. Prosecutors said Rahman tried offering Molotov cocktails to other protesters so they could throw them.

The two were charged in Brooklyn federal court with causing damage by fire and explosives to a police vehicle. If convicted, they face a mandatory minimum of five years in prison.

After Mattis and Rahman spent more than two days in jail, a federal magistrate judge in Brooklyn released them each on $250,000 bond to home confinement with GPS monitoring, describing the allegations as “one night of behavior.”

Prosecutors appealed the ruling twice, calling the two a danger to the community. A federal appeals court sent them back to jail Friday, pending the outcome of their bail appeal.

Police also arrested another woman in Brooklyn, Samantha Shader, who was charged in federal court with throwing a Molotov cocktail at a police car in a separate incident that night. Four officers were able to escape from the car before any injury.

There does not appear to be a connection between the incident with Shader and the one that prosecutors said involved Mattis and Rahman.

Mattis and Rahman most likely met at a birthday party in Manhattan in October 2014, according to a mutual friend. Friends were not aware of romantic involvement between the two but said they were very close.

Rahman’s friends said her roots as an activist seemed evident when she attended Brooklyn Technical High School, one of the most selective public high schools in New York.

Andrea Wangsanata, a high school classmate, recalled that Rahman was often “vocal and adamant, advocating on the side of people who were systematically oppressed.”

Rahman was born in Pakistan and grew up in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, a neighborhood with a large population of Muslim immigrants. The neighborhood came under intense police scrutiny after the Sept. 11 terror attack, which became a defining experience for Rahman, childhood friends said.

Law school friends remembered that she criticized the policing in her neighborhood. In 2014, she co-authored a paper titled, “Changing the NYPD: A Progressive Blueprint for Sweeping Reform.”

Through college and law school at Fordham, she lived primarily at home with her mother. Her father died in 2012.

While Rahman pursued public interest law, Mattis took a more lucrative path.

Martin Guggenheim, one of Mattis’ law professors at NYU, remembered him explaining — “sometimes apologetically” — that he wanted to work at a law firm because he was the first person in his family with the opportunity to have that kind of career.

Mattis grew up in East New York at a time when the neighborhood was among the poorest and most violent in the city. Throughout his childhood, his mother, a Jamaican immigrant who worked as a home health aide and youth counselor at a group home, fostered several children.

He struggled with literacy in the early years of elementary school. By middle school, he became a voracious reader, a neighbor said.

Mattis went to boarding school at St. Andrew’s School in Delaware with the help of Prep for Prep, a competitive program that places high-achieving minority students in private high schools. He later was quoted in the program’s admissions packet as saying he “wanted a better future than that which was offered to me by going to my local high school.”

He was a football player in high school and briefly played rugby at Princeton, where he was also president of the Black Student Union and a member of Cap and Gown, one of the university’s exclusive eating clubs.

His college friends said they were particularly stunned by the allegations because he was known as a peacemaker on campus, the one who brought students of color to parties hosted by wealthy white students.

In recent years, Mattis shared posts on Facebook drawing attention to protests against police brutality and the death of Eric Garner in police custody.

Last summer, Mattis’ mother died of cancer. He moved back to her house in East New York and became responsible for the three children she was fostering, which his half-sister said had been their mother’s dying wish. The children are all under the age of 11.

“He goes to every parent-teacher conference,” said the half-sister, Doreen Crowe.

In recent months, Mattis chatted with friends about ideas he had for improving his neighborhood. He sat on the community board in East New York, focusing on housing.

Bill Wilkins, who serves on the board, had high hopes for Mattis, praising his charm and intelligence. Wilkins noted that the board’s offices were in a Police Department building and that the board had recently facilitated the donation of 5,000 surgical masks to the local precinct, though Mattis had no direct role.

Wilkins, a community activist who described himself as a child of the civil rights movement, said the news of Mattis’ arrest was upsetting.

Wilkins said his hopes for “passing on the mantle” to Mattis seem to have been dashed.

“We need Colin in the struggle,” he said, “but not what he is alleged to be doing.”

Source